What would you do to save the world?

That is, the planet as opposed to the people—we’re the problem, after all—so better, perhaps, to ask: what would you do for a solution? Would you kill your own comrades, if it came to it? Would you sacrifice yourself? Your sons and daughters? Would you betray the whole of humanity today for a better tomorrow?

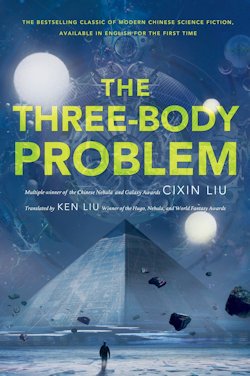

These are some of the provocative questions posed by The Three-Body Problem, the opening salvo of Galaxy Award-winner Cixin Liu’s fascinating science fiction trilogy, which takes in physics, philosophy, farming and, finally, first contact.

But it all begins in Beijing in the 1960s, when Ye Wenjie watches in horror as an unrepentant professor is beaten into oblivion by four fourteen-year-olds “fighting for faith” at “a public rally intended to humiliate and break down the enemies of the revolution through verbal and physical abuse until they confessed to their crimes before the crowd.” The subject of this so-called “struggle session” is Ye’s father, in fact, and his is a death she’ll never forget:

It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race. […] This thought determined the entire direction of Ye’s life.

Indeed, her hatred only grows greater when she’s sold down the river by a fellow rebel a period of years later. Luckily—for Ye if not the whole of humanity—she’s let off relatively lightly; pressganged into service at Red Coast, a SETI-esque radar station in the middle of mostly nowhere—a place associated with a host of strange stories:

Animals in the forest became noisy and anxious, flocks of birds erupted from the woods; and people suffered nausea and dizziness. Also, those who lived near Radar Peak tended to lose their hair. […] One time, when it was snowing, the antenna was extended, and the snow instantly turned to rain. Since the temperature near ground was still below freezing, the rain turned to ice on the trees. Gigantic icicles hung from the trees, and the forest turned into a crystal palace.

When Ye receives a message from the heavens in the form of a warning, at long last she has a chance to put her plans for a moral awakening into action. But is she completely committed to the cause? Or does even Ye have too much to lose?

So goes The Three-Body Problem’s powerful prologue: an unabashedly bold beginning enriched by real human history, set in a time and a place not oft-explored in fiction of any form, and supported by a sympathetic central character with depth and texture.

Would that the whole of the novel was so strong! Unfortunately, the bulk of The Three-Body Problem takes place in what is basically the present day—not ignoring the prologue’s difficult underpinnings but rarely engaging with them in the same refreshingly frank fashion—and casts aside a fantastic female protagonist for man so bland that you’ll cheer when Ye reappears.

At that point, The Three-Body Problem gets interesting again, but in the interim, we’re saddled with Wang Miao, an academic and expert in the development of nanomaterial. “A good man, a man with a sense of responsibility” he may be—unlike Ye—but as a character, he’s unconvincing. He’s married, yet in the entire text he speaks with his wife just once or twice. He’s a hobby photographer—promising, but a plot device, abandoned after it’s served its single purpose. Last but not least, Wang is supposed to be a scientist at the very forefront of his field, however he spends most of the book doing damn near nothing, even when his unique knowledge is called upon.

As a protagonist—of this novel and the next two in the trilogy, I’m told—he’s plain, pedantic, and appallingly passive. I expect he’ll be developed eventually, but if The Three-Body Problem has a problem, it’s with Wang.

That said, even his section has its highlights. The idea that physics is a fiction, which Wang grapples with when he’s invited to join a group of big thinkers at the beginning, is a wonderful one:

Since the second half of the twentieth century, physics has gradually lost the concision and simplicity of its classical theories. Modern theoretical models have become more and more complex, vague, and uncertain. Experimental verification has become more difficult as well. This is a sign that the forefront of physics research seems to be hitting a wall.

There’s also a bit of a murder mystery. See, there’s been a spate of slayings of late; prominent members of the intelligentsia—the same boffins who moments before made Wang so very welcome—are losing their lives left and right, as if someone has set out to systematically spoil humanity’s pursuit of progress. But who would do such a thing? And why?

In search of an explanation, Wang starts playing a VR video game called Three Body, which purports to simulate the existence of a distant alien civilisation struggling under the influence of the mutual gravitational attraction of three suns in a single solar system. These sequences, hard to fathom as they are initially, are among the book’s best and most memorable.

Thus, though Cixin Liu loses his way after The Three-Body Problem’s brilliant beginning, he finds it again in advance of the grand finale, which shifts gears again, immersing us in Trisolaran society: a welcome new perspective considering the alternative.

If you can look past The Three-Body Problem’s uninspiring protagonist—“a man named ‘humanity,’” per the postscript, and perhaps that’s the problem—you’ll find an almost phenomenal first contact novel with riffs on any number of other important issues. Particularly in the prologue, and latterly in the last act, The Three-Body Problem’s setting is tremendous; its science startling; and its fiction, finally, fascinating.

Truly, this trilogy promises profundity, and its beginning comes this close to delivering.

The Three-Body Problem is available November 11th from Tor Books.

Read a series of excerpts from the novel here on Tor.com, and learn more about Chinese science fiction from author Cixin Liu.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.